Health officials are wondering if a tick-borne virus that killed a Warren County woman two years ago is on the rise in New Jersey.

The Powassan virus has “no business being here in New Jersey,” said Tadgh Rainey, Hunterdon County Public Health Division director. But it “now appears to be in Northwest New Jersey.”

A 51-year-old Warren County woman contracted the virus in May 2013. The state Department of Health confirmed later that year that it was the cause of her death.

“I never want to make anyone scared but it’s important to be vigilant.” |

The woman had developed symptoms that included fever, headache and a rash, symptoms eerily similar to Lyme disease, which is also transmitted by ticks. |

According to the federal Centers for Disease Control, in 2013 Lyme disease was the most commonly reported vectorborne (infectious microbe) illness in the U.S. and the fifth-most-common Nationally Notifiable disease.

However, 95 percent of confirmed cases were concentrated in 14 states, mostly in the Northeast and Upper Midwest. New Jersey had 2,785 confirmed cases of Lyme disease in 2013, the fourth highest in the nation following Pennsylvania, Massachusetts and New York.

Unlike Lyme disease, Powassan can cause death. The Warren woman who died also suffered encephalitis, or inflammation of the brain. Powassan virus encephalitis is fatal in about 10 percent of cases.

Powassan is on the rise, according to the CDC, but is still rare, with about 60 cases of the disease reported in the United States over 10 years. It is named for a municipality in Ontario, Canada, near the North Bay, where it was first identified.

Lyme is named for a town in Connecticut.

According to the CDC, Powassan can also cause vomiting, confusion, seizures and memory loss, and may leave survivors with long-term neurologic problems.

Rainey said he first heard about Powassan about six years ago, and didn’t foresee its spread to New Jersey.

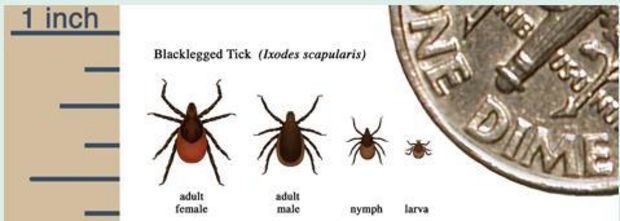

One form of the virus is found in Ixodes cookei or groundhog ticks. A second form, according to the CDC, is found in Ixodes scapularis or deer ticks. Both have transmitted the disease to humans.

Last year, Rainey said his office identified a groundhog tick, which may also be found on dogs, for the first time. He started reading about them, and found there are “more of these groundhog ticks than we ever thought.”

He would like to get a better grasp on how common they are, but noted that’s not an easy task. “Even if we catch them in a trap, they don’t want us pulling ticks off them,” he said. And groundhogs carry and transmit rabies.

But what about the heads of suspected rabid groundhogs brought in for testing? Within an hour of a host animal’s death, Rainey said, ticks flee the body.

So far, he said the only counties to confirm the presence of groundhog ticks in New Jersey are Hunterdon and Monmouth.

He wonders if the Powassan virus has become “more adaptable” over time, allowing it to survive in the “common deer tick we see all over the place.”

If so, it’s too early to tell how that will play out in humans. “It will probably become more common,” but transmission via deer ticks may result in disease that’s less aggressive, or less easily transmitted.

Analogies can be found to mosquitoes, because different species carry different diseases and in different ways.

Another difference with Powassan is that it’s transmitted much more quickly than Lyme, in which a tick usually needs to feed at least 48 hours in order to infect a human. Powassan can be transmitted within hours.

“I never want to make anyone scared but it’s important to be vigilant,” said Rainey, and check thoroughly for ticks after spending time outdoors.

“A lot of these viruses get introduced and it takes a little while to take hold,” he said. He would like to be able to test ticks and “get some baseline information, then predict when a problem” might appear.